Food as a Social-Ecological System

Refining our understanding of what it means to talk about ‘food systems’.

For those who work with and study food, it is now commonplace to talk about the food system and to advocate for taking a food systems perspective. How can we make this systems perspective meaningful in food law research, while being mindful of its challenges? This post describes an approach our group is taking to define the food systems lens and put it to work in food law, policy and governance.

In general, the language of food systems tries to get at the interconnectedness of what is too often treated as a collection of isolated sectors, practices, people, organizations, commodities, policies, regulations and so forth. In food, as in any system, those connections are not just important–they define the system itself. According to a popular primer on systems theory, “a system is a set of things–people, cells, molecules, or whatever–interconnected in in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behaviour over time” (Meadows 2008, 2).

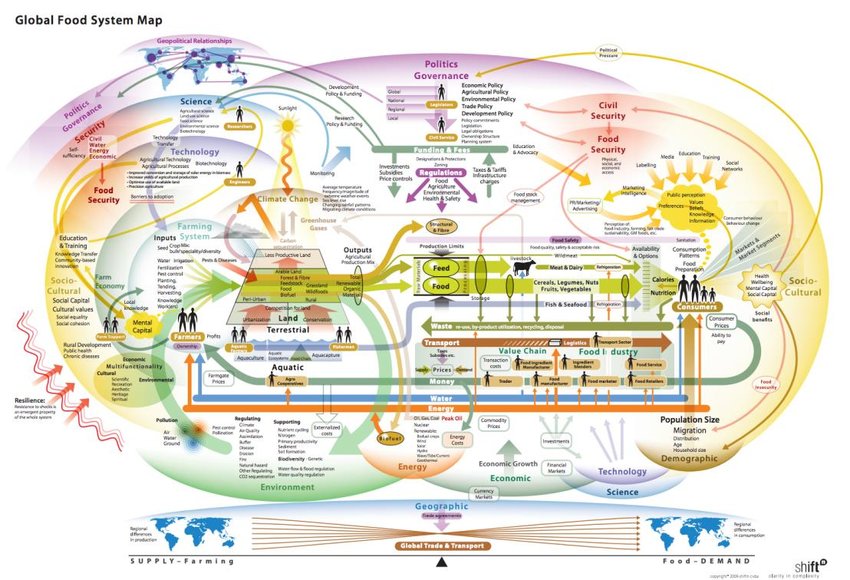

The shift toward systems thinking in food has been a welcome development, driving insights from the potential for agroecological practices to improve local ecosystems and economies [CITE] to the role of food in global geopolitical change (Friedmann and McMichael 1989). But there are also challenges with a systems perspective on food. One familiar problem is that a systems lens can quickly lead from recognizing complexity to becoming mired in it, yielding unruly pictures of the system like this:

Source

Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/pvandenbroeck/global-food-system-map-57053271. Graphic developed as part of (foresight2011?).

The challenge here is to find ways of engaging with the complexity of food systems without oversimplifying–to make complexity manageable for answering the questions we care about.

To achieve this goal, our group is increasingly turning to the frameworks and methods being developed by ecologists and natural resource managers, many of whom are placing the concept of a social-ecological system at the heart of work on sustainability and resilience in their respective fields.

Social-ecological food systems

The food system is not simply a generic system whose parts variously interconnect. Those connections take specific forms that we need to classify in order to understand the system. In reality, foodsheds share some important characteristics with watersheds and other natural resource systems (Kloppenburg, Hendrickson, and Stevenson 1996). Thinking about these as systems with similar structures can help us to move beyond the trap of food systems complexity.

What is a “social-ecological” system?

In the early 1990s, the political scientist Elinor Ostrom published a book called Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Ostrom 1990) in which she showed how local communities of resource users successfully came together to make collective decisions and design rules and norms to avoid the collapse of vulnerable resource systems (the “tragedy of the commons”). Ostrom’s key insight was that rules and norms are crucial to sustainable outcomes and that these rules and norms can, in some circumstances, be generated and enforced by self-governing communities instead of bring imposed by a centralized authority or left to the vicissitudes of the market.

In later work–for which she would go on to win the Nobel Prize in economics–Ostrom and others tried to understand why some scenarios of collective self-governance were successful while others failed. The answer to that question, it turned out, was surprisingly complicated. Rather than success or failure rooted in one or a small number of causes (money, knowledge, etc), it quickly became clear that these outcomes were determined by the dynamics of systems that included natural processes (like rainfall or erosion), social processes (like voting regimes and leadership), and the linkages between them. Such systems would eventually be called “social-ecological systems” (SESs) (Berkes and Folke 1998).

A critical feature of SESs is that they are coupled, adaptive systems. Within any system, the parts interconnect–for example, food systems thinking has long recognized that agricultural regulations are closely linked, through their impacts on food supply, with consumer habits and preferences. But these interconnections–and the policy insights that flow from them–have generally been confined to the social systems affecting food. An SES takes this idea one step further, recognizing that the human and natural components of a larger system feedback and adapt to one another over time. In this model, we need to understand not only agricultural policies and their impact on farmers’ and consumers’ behaviours, but also their possible interrelationships with the natural processes that determine soil health, climate change, and so on.

SES-type thinking has led to several influential policy ideas in the field of natural resource management, the most prominent being a new emphasis on the “resilience” of the system as an end goal rather that specific targets or metrics like the sustainable yield of a forest or fishery (Berkes, Colding, and Folke 2003, 7). Others have argued that “resilience thinking” is a promising route for studying food systems (Hodbod and Eakin 2015).

Components of the Food System

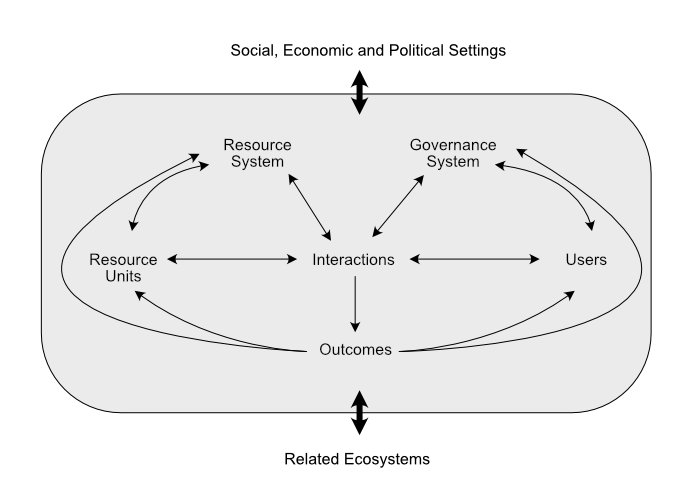

Using Ostrom’s framework, we can start to address the complexity trap in food systems by thinking about an SES as comprised of at least four nested components or sub-systems, connected to one another in the following way:

Source

Adapted from Ostrom (2009).

While the SES framework is potentially adaptable to studying the global food system, it is likely best suited to studying localized food systems in the same way that it has be applied to a local forest, fishery or irrigation system. A “resource system” might be a regional foodshed, while the “resource units” refer to the stocks and flows of crops, animals, products, lands, waters, etc. Users are the individuals who participate directly in the food system (harvest, process, consumption, disposal, etc). And finally, the governance subsystem is comprised of those organizations and individuals who manage the food system, design rules governing access and use, and decide how those rules should be made (Ostrom 2009).

Ideally, we need to understand each of these components and how they fit together in order to understand–and possibly, make predictions or recommendations about–the social-ecological system as a whole. In practice, the many variables involved require us to develop this understanding incrementally. Two of our current projects–Governing Regional Food Systems in Atlantic Canada and Building an Evidence Base for Atlantic Food Policy–focus on the governance system and the system of resource units respectively. We can also usefully break down these systems into additional dimensions, such as by studying the stocks and flows of specific foods or by exploring governance in one sector like food loss and waste. This will always be an imperfect exercise, and while attempts to manage complexity always risk loosing sight of crucial interconnections within the food system as a whole, the SES framework helps to keep our attention directed toward the system’s dynamic rather than static elements.

Sources Cited

Berkes, Fikret, Johan Colding, and Carl Folke. 2003. “Introduction.” In Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change, edited by Fikret Berkes, Johan Colding, and Carl Folke, 1–29. Cambridge University Press.

Berkes, Fikret, and Carl Folke. 1998. Linking Social and Ecological Systems: Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Friedmann, Harriet, and Philip McMichael. 1989. “Agriculture and the State System: The Rise and Decline of National Agricultures, 1870 to the Present.” Sociologia Ruralis 29 (2): 93–117.

Hodbod, Jennifer, and Hallie Eakin. 2015. “Adapting a Social-Ecological Resilience Framework for Food Systems.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 5 (3): 474–84.

Kloppenburg, Jack, John Hendrickson, and G. W. Stevenson. 1996. “Coming in to the Foodshed.” Agriculture and Human Values 13 (3): 33–42.

Meadows, Donella H. 2008. Thinking in Systems: A Primer. chelsea green publishing.

Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons. Cambridge University Press.

———. 2009. “A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems.” Science 325 (5939): 419–22.